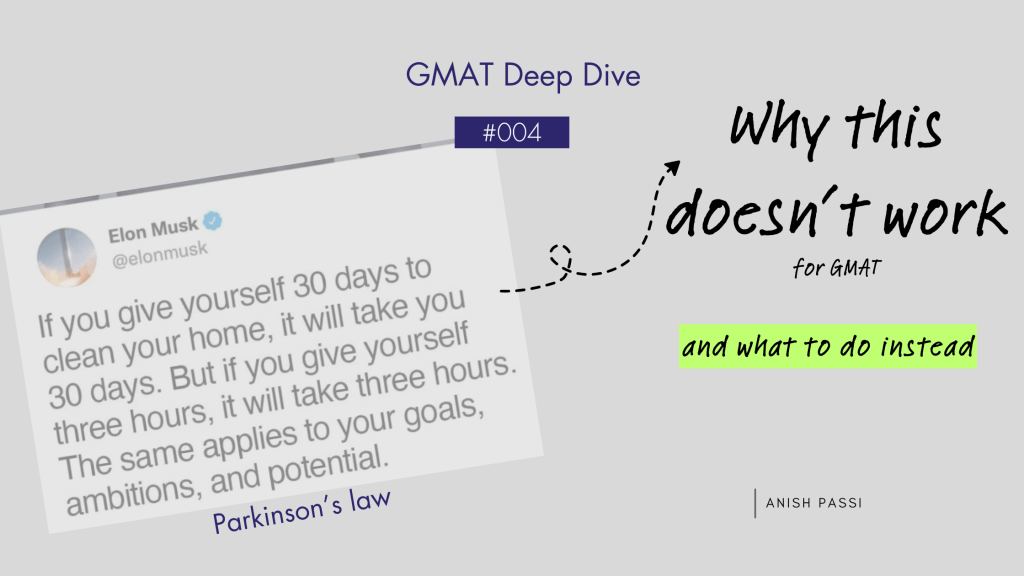

I saw this idea and similar images floating around on LinkedIn:

“If you give yourself 30 days to clean your home, it will take 30 days. But if you give yourself three hours, it will take three hours.”*

In fact, the concept also has a name – Parkinson’s law.

Parkinson’s law: “work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion”

And yes, I see value in this principle in many aspects of my life. However, I feel that preparing with this principle in mind does more harm than good in GMAT preparation.

I’ll take the main quote further. Fine, give 3 hours instead of 3 months, then the task might take 3 hours. But then, why stop at three hours? Why not 30 minutes? Or three minutes? Or three seconds?

You might be thinking: Oh come on Anish! You need to be reasonable.

But therein lies the problem – how do you figure out what timeframe is reasonable FOR YOU?

In this newsletter,

- I’ll explain the issues with how students typically estimate their timelines

- The potential significant side-effects of using such timelines

- An alternate solution that tackles the side-effects

Alright then. Let’s get into it.

Usually how do we calculate how long a task requires?

1. You’ve done the task before

E.g. You know that when you have cleaned efficiently it has taken you 3 hours to clean the home in the past. So perhaps 3 hours is a fair timeframe.

Potential issue: the house should not be significantly more messy than those past times.

In GMAT context: GMAT score is valid for 5 years. It is very rare that a student would prepare for the GMAT, get a high score, and then start preparing for the GMAT again. So, typically no past relevant experience.

2. You’ve done similar tasks before

Say it is a new house. But, you have cleaned houses many times in the past.

Potential issue: Is the house you need to clean now quite similar to the houses you have cleaned before?

In GMAT context: For most people, GMAT is the first exam of its kind. Comparing it with your college exams or other entrance exams doesn't make sense.

3. You are clear about what the various sub-tasks are and how long each would take

3 hours estimate could be calculated by having a good estimate of the time subtasks would take.

e.g.

- Kitchen

- Wash, dry and store utensils – 30 minutes

- Clean the shelves and cooking counter – 15 minutes

- Clean the floor – 15 minutes

So, kitchen: 1 hour. And similarly, others could be figured out.

- Washroom: 1 hour

- Bedroom: 30 minutes

- Living room: 30 minutes

Potential issue: There could be sub-tasks that you did you consider. Your estimate timeframes of some sub-tasks could be off.

In GMAT context: This is typically not how test-takers figure out timelines. They don't look at the subtasks? And for good reason.

Do you know how long Critical Reasoning would take? How long the whole Verbal would take? Algebra? 2-part analysis? There's no formula that tells you: CR takes 15 hours, algebra takes 20 hours, it takes X hours to go from score A to score B… It's not that simple.

Moreover, it is difficult to create a comprehensive list of sub-tasks. There are various sections and question types. But, maybe you need to work on becoming a better test-taker too. Maybe stamina is a factor for you. Have you included that as a sub-task?

4. You look at how long others usually take to do the task

It can help get a rough timeframe

Potential issues:

- Is my house a similar size to the ones I am comparing with?

- Am I as skilled at cleaning homes as others?

- Do I have similar tools to clean my home as the others?

I find that GMAT candidates typically figure out their timeframe by looking at others. Things like:

- How long did colleagues/ friends take?

- How long do people who share their GMAT stories on the internet typically take?

- Google search: How long does it take to ace the GMAT? And then looking at figures mentioned by test-prep companies.

People often take anecdotal evidence or combine the pieces to figure out a rough “average” to establish their timeline.

Now, one issue with this approach is how do you know others’ timelines or the rough average apply to you?

The time you’d take depends on a multitude of factors – quality of study, time devoted to study, process you follow, your mindset with regards to study, etc.

I haven’t even mentioned perhaps the biggest one yet. Can you guess it?

Your starting level!

Not everyone starts at the same level. So how can everyone take the same amount of time?

Moreover, GMAT tests something new. Familiar, yet new. So, just macro factors such as education background, marks in school, etc do not do a good job of highlighting your starting level.

That’s not all though. There is a nuance that makes this data available online about timelines very suspect.

I’ll explain with a story.

A student went from 460 to 640 on the GMAT in 9 months. (old scoring system). I asked him to write about his 'success story' on GMAT club.

He said that he was apprehensive because 640 is not a 'great' score.

I was taken aback. In those 9 months,

1. He had suffered from dengue and jaundice.

2. He did not prepare for the GMAT full-time.

3. His father had fallen seriously ill.

4. He had improved by 180 points.

That's inspirational, no?

Yet, he believed that his story and his score were not worth celebrating.

Why?

Because typically the top b-schools' average scores are higher.

Because others often aspire for a 700+ score.

Because 640 is considered a 'low' score.

I believe that the people who share their GMAT stories online represent a very specific subset of GMAT test-takers.

- A person who gets a great score within a short time would typically be comfortable sharing their journey online.

- A person who takes much more than the average/ typical/ general time to get a great score would typically be less motivated.

- A person who gets a decent but less than great score would typically not be as motivated.

- A person who doesn’t end up with a decent score would typically not share their journey online at all.

Even test-prep companies have an incentive to highlight such misnomers. It becomes a marketing tactic:

“With us, you can ace the GMAT in 45 days!”

If you ever see a test-prep company advertise this way, ask them: Do you guarantee it? If I follow everything you say, yet don’t ace the GMAT within your specified timeline, will you refund my money?

I submit:

The data available online is highly skewed and represents a very narrow cross-section of all GMAT takers.

The Real Cost of Generic Timelines

When students that numbers like “3 months” or “100 hours” apply universally, it creates two major problems:

- You rush through concepts without mastering them.

- You finish the syllabus in three months but still can’t solve 605 / 655 level questions.

- You don’t finish on time and start questioning yourself.

- “Am I just dumb? Why did everyone else finish in three months?”

But the truth is, not everyone finishes in three months. Many people take longer. They just don’t talk about it.

Now, one contention in favour of having a stringent timeline is:

I’ll aim for 3 months. I’ll at least be done within 6. But if I instead target 12 months, then I’ll anyway take at least 12 months.

Consider this: Say I tell you that it typically takes 3 months to build a house. You start building the house. Now, ideally you should focus on the foundation properly first, and then move on only when that stage is done. But, if you have an arbitrary deadline in mind, after 15 days, you might think: “I have already spent half a month at this stage. I need to build a 5-storey building. I can’t afford to spend so long on just the foundation stage. I’ll move on to the next floor. I’ll come back to the foundation later – if needed.

That’s a big problem, no? If the task is sequential: foundation, then ground floor, then the higher floors – you can’t keep coming back to interim stages. It makes sense to go through each stage properly in one go.

If you are willing to evaluate your progress and tweak your expectations – fine. Then set any timeline initially. But, if you are looking at 3 months as a timeline to fit all your preparation into, it’ll probably hinder your prep more.

Ok … so, say I have convinced you that creating timelines initially is not very productive. Then you might wonder: so do I just go in completely blindly? Wouldn’t my work just keep expanding? That way GMAT prep could go on forever.

I don’t think so. To explain, first let’s understand why do students even seek timeframes?

Why we seek timelines

The appeal of deadlines is understandable – they seem to provide structure, motivation, and a sense of urgency. Essentially, they can help you stay motivated.

So, if the purpose is to push yourself, but there are significant inherent disadvantages, then the question becomes: can I push myself using some other approach that doesn’t have these disadvantages?

Here’s what I suggest:

Track Weekly Progress Instead

Forget arbitrary deadlines. Instead, track weekly progress:

Instead of fixating on a deadline, focus on how much you get done each week. Here’s what to do:

- Plan your study week in advance.

- At the end of the week, evaluate:

- How many hours did you plan to study?

- How many hours did you actually study?

- How much material did you expect to cover?

- How much did you actually cover?

- Use this data to plan the next week.

If you consistently miss your targets, don’t just “try harder.” Instead, re-evaluate what is realistic for you. Maybe you need to schedule fewer study hours. Maybe you need to cover fewer topics per week. The goal is to set yourself up for success, not to chase an arbitrary deadline.

Consider a longer horizon

Start with a 12-month horizon rather than a compressed timeline. Don’t wait until you’re just 3 months away from application deadlines to start preparing for the GMAT.

Your GMAT score is valid for five years. If you finish ahead of schedule, great—there’s no downside. It’s a myth that a more recent score is preferred; all valid scores are treated equally.

P.s.: I’m not saying that you definitely won’t require more than 12 months. I know too many people who have been preparing for the GMAT for over 24 months.

What if you can’t afford 12 months?

Sometimes, it just turns out this way. You finally decide to start preparing for the GMAT, and there are only 3 months left before application deadlines. What to do?

Then, adjust your expectations. Instead of saying, “I must hit my target score in three months,” shift your mindset to:

- “I will improve as much as I can in the next three months.”

- “I will keep preparing beyond three months if needed.”

It’s like fitness. You can set a goal to get as fit as possible in three months or a goal to get six-pack abs no matter how long it takes. But setting a goal like “I must have six-pack abs in three months” is arbitrary – it depends on where you’re starting.

That’s it for today.

*I have seen this quote attributed to Elon Musk often. I am not certain of its origins though.

Subscribe to the newsletter

[…] Focus on the process you’re following and your inputs today. The outcome will follow automatically. I elaborate on this point in these articles: Stop all this beginner nonsense and Why Parkinsons law doesn’t work for GMAT prep. […]